Why Were Goats Only Domesticated In Mesopotamia? What Made This Animal Useful?

Agriculture is the ratio chief economic activity in ancient Mesopotamia. Operating nether harsh constraints, notably the arid climate, the Mesopotamian farmers developed effective strategies that enabled them to support the development of the starting time states, the first cities, and then the first known empires, nether the supervision of the institutions which dominated the economy: the royal and provincial palaces, the temples, and the domains of the elites. They focused in a higher place all on the cultivation of cereals (particularly barley) and sheep farming, but also farmed legumes, too every bit date palms in the south and grapes in the n.

In reality, there were two types of Mesopotamian agriculture, corresponding to the two main ecological domains, which largely overlapped with cultural distinctions. The agriculture of southern or Lower Mesopotamia, the state of Sumer and Akkad, which subsequently became Babylonia received near no rain and required large scale irrigation works which were supervised by temple estates, just could produce high returns. The agriculture of Northern or Upper Mesopotamia, the land that would eventually become Assyria, had plenty rainfall to allow dry out agriculture most of the time and so that irrigation and large institutional estates were less important, only the returns were as well usually lower.

Climate [edit]

While developing models to describe the early on evolution of settled agronomics in the Well-nigh East, reconstructions of climate and vegetation are a bailiwick of consideration. During the glacial period, information technology is thought that lower temperatures or higher aridity resulted in thin or not-existent forest cover similar to steppe type terrain in the area of the Zagros Mountains and varying forest cover in the territories of modern-day Turkey and Syrian arab republic. Northwest Syria, dominated in ancient times by deciduous oak, is idea to have been less arid betwixt 10,000 BCE and 7000 BCE than it is today. Scholars believe that wild cereal grasses probably spread with the forest comprehend, out from the glacial refugia westward into the Zagros.[1]

Topography [edit]

The Tigris flowing through the region of modern Mosul in Upper Mesopotamia.

The societies of ancient Mesopotamia developed one of the almost prosperous agricultural systems of the ancient earth, nether harsh constraints: rivers whose patterns had petty relation to the growth cycle of domesticated cereals; a hot, dry climate with brutal interannual variations; and generally sparse and saline soil. Conditions in the north may have been more favourable because the soil was more than fertile and the rainfall was high plenty for agriculture without irrigation, but the calibration of rivers in the south and the flat plains which made it easy to cut irrigation channels and put big areas under cultivation gave advantages to the development of irrigated farms which were productive but required constant labour.

The native wild grasses in this region were densely growing, highly productive species, specially the varieties of wild wheat and barley. These grasses and wild legumes like pea and lentil were used as food sources in the hunter-gatherer societies for millennia before settled agronomics was widespread.[1]

Rivers [edit]

The two principal watercourses of Mesopotamia, which requite the region its name, are the Euphrates and the Tigris, which period from Anatolia to the Farsi Gulf.[2] [three] The Euphrates is around 2,800 km long and the Tigris is about ane,900 km. Their regime is of the pluvial-naval type, with loftier flow in bound as a result of melting snow and when rains fall in Upper Mesopotamia. This is more than accentuated with the Tigris, which receives several tributaries from the Zagros during the second part of its form, while the Euphrates has only a pocket-sized tributary in Upper Mesopotamia. Thus its output is weaker, especially since information technology crosses flatter areas and has a wide bend in Syria which slows its flow. Floods of the rivers thus take place in spring - in April for the Tigris and in May for the Euphrates (presently later on or during the harvest). Their baseflow occurs in summertime at the fourth dimension of greatest estrus, when evapotranspiration is very high, especially in the south. The variability of menstruum rate over the twelvemonth is very smashing - up to 4:i. The discharge of the Euphrates and its floods were weaker than those of the Tigris, so it was on particularly on its banks that agricultural communities of southern Mesopotamia focused. In this region, the ground is very flat, leading to bifurcation, which results in islands and marshes, too equally sudden changes of course, which occurred several times in antiquity. Both rivers conduct silt which raised them above the level of the surrounding plain, making it easy to irrigate the land surrounding them. However, it also meant that their floods had the potential to cause serious impairment and could embrace a vast area. The flatness of the region besides meant that the phreatic zone and the stream bed were very close, causing them to ascension in periods of flooding. In modern times, the Tigris and the Euphrates join to form the Shatt al-Arab which so debouches in the Persian Gulf, but in antiquity, their delta did not accomplish so far south, because it was created slowly by the deposition of alluvium.[4] [5]

Other watercourses in Mesopotamia are the rivers that flow into the Tigris and Euphrates. The tributaries of the sometime originate in the Zagros; from north to south they are the Neat Zab, the Lilliputian Zab, and Diyala. Their courses have a rapid menstruation, on business relationship of the steep relief and the gorges through which they flow, as well as the snowmelt in jump which leads to large floods in April/May. They carry a big amount of the alluvium which ends upward in the Tigris. The Euphrates has 2 tributaries which see it in southern Jazirah: the Balikh and the Khabur.

Relief [edit]

Typical view of farmland in the area north of Al-Hasakah, with an aboriginal tell visible on the horizon

The terrain of Mesopotamia is by and large apartment, consisting of floodplains and plateaus. It is bordered past high mountains on the eastern side - the Zagros range, which is pierced by deep valleys and canyons with a northwest-southeast orientation (Great Zab, Little Zab, Diyala) - and past smaller mountains and volcanoes in Upper Mesopotamia (Kawkab, Tur Abdin, Jebel Abd-el-Aziz, Sinjar, Mount Kirkuk). Essentially, Upper Mesopotamia consists of plateaus which are slightly inclined to the east, ascent from 200–500 m in altitude, and which are now known every bit Jazirah (from the Arabic, al-jazayra, 'the isle'). Thus, the rivers catamenia through valleys which are ane–x km wide. The southern half of Mesopotamia, which is the role properly called Mesopotamia from a geophysical point of view, since it is where the Tigris and Euphrates flow close to one some other, is a vast plainly, which is 150–200 km wide and has just a very slight incline, decreasing to the due south until information technology is almost not-existent. This encourages the development of river braiding, sudden changes of course, and the institution of marshy areas.[six]

Soil [edit]

The soil in Mesopotamia is mostly of the sort that is normal in barren climates: a shallow layer on elevation of the boulder which is not very fertile. They are generally composed of limestone or gypsum with nutritive elements which enable plant growth, but have simply a narrow layer in which the roots can abound. Deeper soil is found in the valleys and culverts of Upper Jazirah. In the more arid areas of Lower Jazirah and Lower Mesopotamia by dissimilarity, the soil is generally sparse and very shallow (solonchak and fluvisol types) and mostly composed of gypsum. They dethrone hands and irrigation accelerates both their erosion and their salinisation.[seven] [8] Nonetheless, the poverty and fragility of the soils of Southern Mesopotamia are largely compensated for by sheer surface area of apartment land available for irrigation. In the due north by contrast, there is ameliorate soil, but less country and in that location is more than risk arising from the variation in precipitation.[9]

Homo infrastructure [edit]

Mesopotamian farmers did a number of things in guild to augment the land's potential and reduce its risks. The infrastructure that they created greatly altered the state, especially through the cosmos of irrigation networks in the south where the supply of h2o from the river was necessary for the growth of the crops. Thanks to textual sources it is partially possible to reconstruct the advent of the Mesopotamian countryside and the different types of land exploited by the farmers.

Irrigation [edit]

The first archaeological signs of irrigation in Mesopotamia appear around 6000 BC at Choga Mami in central Mesopotamia, during the Samarra culture (6200-5700 BC). Mesopotamia southward of this site is very poorly attested in this period - it is possible that the first communities adult there at the same time and too made use of irrigation. Survival was only possible with the use of an irrigation system, since without it the viable agricultural area in this region was limited to the banks of the two great rivers. Canals were cutting to bring the h2o that was needed for the plants to grow to the fields, only too to divert water and thus limit the damage from floods. When the h2o level was high, the larger canals became navigable and could be used for merchandise and communication. Irrigation was also adopted in areas where it was not absolutely necessary, in order to increase yields. Communities and rulers fabricated the maintenance, repair, and dredging of irrigation infrastructure one of their highest priorities.

The h2o for irrigation was brought to the fields by canals.[ten] The largest of these were fed directly from the rivers and supplied water to smaller canals which supplied yet smaller channels, all the way down to small irrigation ditches. The system could besides include raised canals and sometimes aqueducts, if the terrain required them. Some regulating mechanisms were in place to control the menstruum and the level of the water, such as closeable basins. The sediment carried in the rivers meant that their beds were college than the fields on the floodplain, so the water could be brought to the fields using gravity lone, once a ditch had been cut in the side of the riverbank.[11] [12] Withal, mechanisms for raising water, like the shadoof and the noria, were in use from the showtime millennium BC. In some regions irrigation could also be effected from wells.

The irrigation network of Mari is well known from descriptions on small tablets from the first half of the 18th century BC relating to maintenance work and thus provides a useful case study. The tablets mention the 'mouth' (KA/pûm) where the h2o from the river entered the canal and deposits of dirt had to be removed. The basic construction at this level was the muballitum, a mechanism which controlled the menstruum of water from the river and thus the water level of the canal. It was a barrier made out of wooden piles (tarqullum), reinforced with bundles of reeds and brush. The primary canals (takkīrum) are distinguished from the minor calls (yābiltum) which catamenia from them. Valves (errētum) on the sides of the canals allowed water to be let out if the level rose too loftier. Ditches (atappum) were located at the stop of the canal. Dams (kisirtum) were used to store water. Secondary basins were fed by terra cotta pipes (mašallum). Maintenance of the canal was very intensive work: according to one alphabetic character, the governor of the district of Terqa had to mobilise almost two,000 men for the task and information technology seems that this force proved insufficient.[thirteen] [14]

Fields and state segmentation [edit]

Various cuneiform documents contain descriptions of fields; nigh a hundred also draw field plans. The most common of these are small tablets. From the introduction of writing, the locations of fields were recorded. Under the Third dynasty of Ur, the showtime tablets appear with plans of fields which they depict. They were designed to help evaluate the returns that could be expected from the fields. As fourth dimension went on, these descriptions grew more than precise. The Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid periods have furnished numerous documents of this type - some every bit tablets, but others every bit Kudurru (engraved stelae produced subsequently a country grant). By and large, measuring and recording land took place when it was sold. The most precise texts specify the measurement of the sides, the owners of neighbouring plots, and split up the field into different parts based on the returns expected from them. Some of these documents may have been intended to inform people of the measurements made by surveyors and the estimated yields. The calculations of the expanse of a field are made by approximating the real shape of the field with regular geometric shapes which were easier to calculate - a rectangle for larger areas and triangles for any irregularities. The actual surveying was done with ropes (EŠ.GID in Sumerian, eblu(m) in Babylonian Akkadian, ašalu in Assyrian Akkadian). Surveyors are attested as specialised members of the regal administration in Ur Three and the Quondam Babylonian periods.[15]

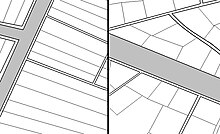

Representation of 'Sumerian' (left) and 'Akkadian' (right) field types, as proposed by Mario Liverani.

Through the analysis of these documents it is possible to reconstruct the advent and location of the fields in ancient Mesopotamia. Fields in irrigated areas had to have direct access to a canal. This led to competition for access to the water sources and the width of fields was reduced in lodge to permit a larger number of them to cluster along the sides of the canals - a field was fabricated larger by extending the length that information technology stretched away from the canal. The resulting fields were roughly rectangular, but much longer than they were broad, like the strips of woods in a parquet floor. According to Mario Liverani, this was the field layout establish in Sumeria. Further north, around Akkad, the fields were wider - at least until the first millennium BC, when the elongated field layout seems to have spread to Babylonia as well. Liverani also argues that this layout was the result of central planning, designed to make optimal use of the area by ensuring the largest possible number of fields had access to the canal (and thus he attributes the spread of this blazon of layout to decisions of royal authorities). Zilch like this layout is known from Upper Mesopotamia, except for the state around the city of Nuzi, where both elongated and broad fields are attested.[sixteen]

Hypothetical program of a village's hinterland in aboriginal lower Mesopotamia.

In the areas of irrigated agriculture in the south, therefore, it was the irrigation canals that created the structure of agricultural land. The raised banks of the rivers were densely occupied spaces: Palmaries and orchards which needed to be close to the canals in society to exist properly irrigated were located there, as were the villages. The most densely developed areas were located at the edge of the villages which formed the heart of the canal network (since the centres of these settlements were given over to non-agronomical purposes). As a canal stretched to the arid land at the edge of the irrigated expanse, the area that the canal was able to provide water to decreased, as did the quality of the soil. Uncultivated land was used to pasture farm animals. The edge of the irrigated area could too be formed by swampland, which could be used for hunting and fishing, or for growing reeds (particularly in the far due south of Mesopotamia).[17] [18] The line between the irrigated land and the desert or swampland was not static: fields could fall out of cultivation because there was as well much salt in the soil and and so desertification would follow; on the other hand, desert land could be brought under cultivation by extending the irrigation network. Similarly, marshland could be tuckered or aggrandize at the edge of a recently irrigated surface area or following changes in the river's course.

In Upper Mesopotamia, areas of dry agriculture (Upper Jazirah and east of the Tigris) must be distinguished from those where irrigation was e'er required (Lower Jazirah). From the latter situation, the site of Mari is well-known, thanks to surviving texts: the cultivated zone was located on the low terraces of the Euphrates valley, where irrigation networks were developed, while the higher terraces were used for pasture, and the area furthest from the river (up to fifteen kilometres abroad) was a plateau that could be used for livestock.[19] The topography of the north did not allow irrigation networks to extend equally far as the broad flat plains of the southward.

In the areas of dry agriculture in the Upper Jazirah, from the 4th to the 2nd millennium BC land was organised around fortified centres with a round shape located on high points. The agricultural infinite around these centres was organised in concentric circles in a manner described by T.J. Wilkinson: a densely cultivated expanse around the fortified centre, and then less intensely cultivated areas around secondary sites and finally a space used for pasturage.[20] [21] Because of the irregular rainfall, some areas of dry out agriculture in the north came to be irrigated. For case, the countryside around Nuzi included both unirrigated and irrigated fields.[22]

Archaeological surveys seem to indicate that the organisation of rural space in northern Mesopotamia changed at the end of the 2nd millennium BC, in line with the evolution of the Assyrian empire. The farmed area expanded and the Assyrian kings extended irrigation networks and gardens in many areas (particularly around Nineveh).[23] [24]

Rural settlements [edit]

Texts and to a bottom degree archaeological survey allow us to discern the outlines of settlement in the Mesopotamian countryside.[25] [26] [27] By contrast there has been little archaeological excavation of rural settlements of the historical period, since the focus has been on urban centres.

It seems that for the bulk of its history, people in Lower Mesopotamia mostly lived in cities and the ascension of hamlet settlement only began in the second half of the second millennium BC when sites of more two hectares constitute more than a quarter of known settlements. This 'ruralisation' of Babylonia continued in the post-obit centuries. A large portion of the farmers must have resided in urban settlements, although some of these were quite small - surface surface area cannot decisively distinguish villages and cities (a site like Haradum, which is considered to be a city because of the buildings constitute in it, covered only ane hectare). Even so, texts point diverse types of rural settlement, whose verbal nature is not easy to define: the É.DURU5 /kapru(one thousand) were some sort of hamlet or large farm, only some settlements that seem to be villages were referred to with the aforementioned terms used to refer to cities (particularly URU/ālu(m)). The but definite 'village' that has been excavated in the south is the site of Sakheri Sughir near Ur, which dates to the primitive period, just only a very small area of the site has been excavated and only a few parts of buildings accept been identified.[28] Elsewhere, rural people are attested in texts living in isolated brick farmhouses, camps of tents similar nomads, or in reed huts (huṣṣetu(g)) that were feature of the south. There were also centres - frequently fortified - which served as centres for the exploitation of large areas (dunnu(m) and dimtu(yard), the latter literally significant 'tower'). An case has been excavated in the Balikh valley at Tell Sabi Abyad which is a walled settlement measuring 60 x 60 metres containing a master's firm, a steward'due south house, some administrative buildings, and a few other structures. Salvage excavations in the Hamrin basin in the Diyala valley have partially revealed several similar centres from the Kassite menstruation, containing workshops of artisans (peculiarly potters): Tell Yelkhi (a kind of rural manor), Tell Zubeidi, and Tell Imlihiye.[29] [30] Other things were also congenital in rural areas, such as cisterns, threshing floors, and granaries.

Risk management [edit]

The administration of the Mesopotamian countryside was as well motivated by a desire to amend various kinds of gamble that could affect agricultural activities and rural and urban society more than generally. The irrigation system was also designed to limit the risk of floods, by means of basins that could retain backlog water and canals that could drain information technology away, as well every bit dams. The fragility of the soil, particularly in the south, also required management and specific cultural practices to protect information technology. The most uncomplicated of these was the practise of crop rotation, which was not hard since there was no shortage of cultivable land in the region. The choice of crops and animals that were adjusted to the dry out climate and poor soils (barley, date palms, sheep) was another solution to this problem. The layout of the fields seems to take been designed to protect them from erosion: lines of trees were planted at the edges of the cultivated area to protect information technology from the winds, some areas were left dormant then that the plants and weeds would grow there and protect the soil from wind erosion.[31] The practice of combining palm orchards and gardens enabled the large trees to protect smaller plants from the sun and harsh winds.

The largest problem for farmers in the south seems to have been the salinisation of the soil. Thorkild Jacobsen and Robert McC. Adams have argued that this caused an ecological crisis in Babylonia in the 18th-17th centuries BC. If this trouble was really caused by the high table salt content of the soil and their irrigation arrangement brought a ascent corporeality of common salt-carrying water to the surface, then the aboriginal Mesopotamians seem to have developed techniques that ameliorated this result: control of the quantity of water discharged into the field, soil leaching to remove salt, and the practise of leaving state to lie dormant. It is not sure that the salinisation of land in southern Mesopotamia really did atomic number 82 to a fall in output and crunch in the long-term, merely it did constitute a constant year-to-yr problem.[32]

Some other recurrent risk for Mesopotamian farmers was influxes of insects, peculiarly desert locusts, which could fall upon the fields in large numbers and devour all the crops. The governors of Mari fought them with h2o from the canals, trying to drown their larvae and bulldoze off the adults, or by getting men and beasts to crush them.[33]

Crops [edit]

Mesopotamia had been on the margin of developments in the Neolithic and the origins of agriculture and pastoralism took identify in Mount Taurus, the Levant, and the Zagros, only information technology conspicuously participated in the second phase of major changes which took identify in the Near East over the course of the quaternary millennium BC, which are referred to as the '2nd agricultural revolution' or the 'revolution of secondary products' in the case of pastoralism.[34] [35] These changes were characterised by the expansion of cereal cultivation post-obit the invention of the plough and irrigation; the expansion of pastoralism, specially the raising of sheep for wool, but also beasts of burden such as cattle and donkeys, and dairy animals; and cultivation of fruit copse, such as date palms, olives, grapes, etc. They were accompanied by the establishment of the start states, the first cities, and these institutions possessed vast fields of cereals and great herds of sheep.

From this fourth dimension forward, the Mesopotamians possessed a great diversity of agricultural products and also a significant quantity of domestic animals. This ensemble continued to be augmented over the millennia past imports from exterior Mesopotamia and by local innovations (comeback to tools with the rise of metallurgy, new breeds of institute and animal, etc.). Throughout antiquity, agricultural produce centres on some bones elements, notably barley and sheep (forth with date palms in the southward). Simply gardens enabled the diversification of nutrient sources, cheers especially to legumes. It must exist remembered that ancillary activities like hunting, fishing, the exploitation of marshes and woods, were necessary complements to agronomics.

Textual sources include significant evidence for the rhythms of farming and herding, but the vocabulary is often obscure and quantification is difficult. The study of archaeological evidence to identify the remains of plants and pollen (archaeobotany and palynology)[36] and animals (archaeozoology)[37] consumed at ancient sites is also necessary. Much is still unknown, but recent studies, particularly those published in the viii volumes of the Bulletin of Sumerian Agriculture, have considerably avant-garde our knowledge.[38]

Cereals [edit]

Field of cereal nigh the Euphrates in the northwest of modernistic Iraq.

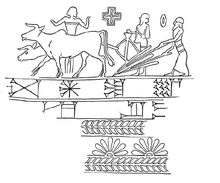

Seal impression from the Kassite period (tardily 14th century BC), representing a group of labourers pulling a plough.

Mesopotamia is a keen cereal producer. Most important were barley (Sumerian ŠE/ Akkadian še'u(m)), because it was the best adapted to the dry, saline soil and to the hot temperatures of the region, while its short growing cycle meant it could reach maturity even in particularly hot, dry out years. It was the master food of the population and was ofttimes used every bit a medium of exchange. Emmer wheat (ZIZ/zizzu(chiliad)) was also cultivated, but in smaller quantities, every bit well as spelt (GIG/kibtu(one thousand)). In the 1st millennium BC, rice (kurangu) was introduced, but was not very widely cultivated.[39] [forty]

Barley [edit]

A Sumerian text known as the Farmer's Annual (or Instructions of the Farmer)[41] informs us about the techniques employed to cultivate barley in southern Mesopotamia. This information tin be supplemented with that available in the agricultural direction texts. The agricultural year is divers by several periods of intense piece of work and other necessary maintenance of the fields:[a]

- Firstly, towards the end of summertime (Baronial–September), the field must be irrigated in order to loosen up the desiccated soil after the summer heat. And so, at the beginning of autumn, work begins on the preparation of the soil. The plough employed is the ard (APIN/epinnu(grand)), fatigued past iv oxen, arrayed 2-by-ii. The ard reaches only 15–twenty cm into the earth, only this is sufficient in the sparse soil of southern Mesopotamia. If necessary, however, the work could be completed with a hoe (AL/allu(k)) and a spade (MAR/marru(m)).

- Sowing then took identify in the autumn (largely in October–November). A prior approximate of the quantity of grain that ought to be sown was carried out in guild to ensure optimal production. The seeds and beasts of burden were prepared, and teams of labourers were formed. The ploughs were equipped with a seeder - a kind of funnel designed to leave the seed buried behind the plough as information technology turned the soil. The grain was planted at regular intervals of around lx–75 cm.

- At the finish of autumn and during the winter, the field needed to be weeded and irrigated repeatedly. Plainly, no other techniques for improving the soil were undertaken at this time. The animals were removed from the seeded fields in gild to avoid dissentious them.

- In jump (April–May), the harvest began, just before the river level began to rise, or at the same time. This was a period of intense labour. The ears of wheat were cut with ceramic, stone, and metal sickles. The ears of wheat were collected in threshing areas where the grain was separated from the crust using a threshing board (a wooden board pulled by oxen of donkeys, with flints attached, which separates the grain from the stems and cut up the straw), then winnowed. It is at this moment that the harvest is distributed between the different actors, in lodge to settle debts and pay rents. Then the grain is placed in storage, in June–July at the latest.[42] [43] [44] [45]

Cultural practices served to protect the productivity of the fields, especially from the danger of salinisation in the south. Biennial ley farming was mostly practiced and sometimes fields were left fallow for longer periods of fourth dimension. The soil was also washed regularly in society to expel the table salt. Crop rotation may besides have been expert.[31]

Date palms [edit]

Palm orchard in modern Iraq, near Baghdad.

The tillage of date palms (GIŠ.GIŠIMMAR/gišimarru(k)) played a major part in the due south. This tree requires a lot of water and is naturally constitute along the edge of watercourses. It thrives in saline soils and high temperatures. Thus, conditions were very favourable for its development in lower Mesopotamia. The palm was cultivated in keen palm orchards, which are represented in bas reliefs from the Neo-Sumerian menstruation. They were irrigated and divided into multiple groups of trees that had been planted at the same fourth dimension. The palm only begins producing dates (ZÚ.LUM.MA/suluppū(m)) in its fifth year and lives for nearly sixty years. Developing a palm orchard was therefore a medium-term investment and an orchard needed to be supplemented regularly by planting new trees. The Mesopotamians developed an artificial pollinisation system to maximise their return - the male pollen was placed on the female stamens at the superlative of the tree by paw with the aid of a ladder.[46]

Other field crops [edit]

In addition to the cereals, other crops were cultivated in the irrigated fields, merely played a less central part. They were sometimes referred to as 'minor' crops (ṣihhirtu(m)) in the Old Babylonian period.[47] They include many plants:

- Flax (GADA/kitū(m)) was apparently not much cultivated in Mesopotamia before the 1st millennium BC, although it had been well-known since the Neolithic. It was mainly used for producing linen textiles, but its grains could also be eaten or used for the production of linseed oil.[48]

- Sesame (ŠE.GIŠ.Ì/šamaššammū(m)) was the most important ingather grown in the fields later on cereals. It was introduced to Mesopotamia around the end of the tertiary millennium BC, from Bharat. Information technology required irrigation to grow. The seeds were planted in jump and the harvest took place at the finish of the summertime. It was used to produce sesame oil, which was used for nutrient, hygiene, and equally fuel for lamps. The seeds could as well exist eaten.[49] [50]

- Various legumes, such every bit chick peas (hallūru(m)), vetch (kiššanu(one thousand)), and other kinds of pea, lentil, and beans were an of import supplement to the cereals.

- Onions were too grown in the fields.

Garden and orchard crops [edit]

In the gardens/orchards (GIŠ.KIRIvi /kirū(m)), which were sometimes incorporated into the palmeries, there were diverse vegetables. which do not seem to have been focussed on a specific type of cultivar. The most usually attested are green leaves, cucumbers, leeks, garlic, onion, legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans), and various kinds of herbs. In that location were also fruit trees, peculiarly pomegranates, figs, and apples, but also quinces and pears. The gardens of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian kings included a very corking variety of crops, which are enumerated in texts that celebrity in these kings ability to join plants from throughout their domains. In item, they fabricated efforts to acclimatise the olive and cotton.[51] [52] [53] [54] [55]

Vines [edit]

Grape vines abound mainly in the north of Mesopotamia and were not widespread in the southward, where the climate is not favourable for them. Several Sumerian texts indicate that they were constitute in orchards, but but at their edges. On the other manus, vines were common in Upper Mesopotamia. In the 18th century BC, there was a cite south of Djebel Sindjar named Karanâ, which literally means "wine" (karānu(m) in Akkadian; GEŠTIN), indicating that there were many vines growing on the slopes of the hill. Documentation on wine is particularly rich for the Neo-Assyrian period, when the kingdom'south high dignitaries possessed substantial wineries, every bit attested by a cadastral document relating to territory near Harran. In the same menstruation, distributions of wine were a mutual feature of life at the royal courtroom. Grapes could exist consumed as food or converted into wine. The procedure of winemaking is not attested in Mesopotamian texts. Wine is attested, but was boozer less often than beer, which remained the principal alcoholic drink of Mesopotamia. Instead, wine was a luxury product, with the best vintages produced in the mountainous regions bordering Mesopotamia (Syria, eastern Anatolia, the Zagros mountains), and imported past the Mesopotamian majestic courts, which seems to indicated that the wine produced in Mesopotamia itself was of comparatively low quality.[56] [57]

Animal husbandry [edit]

Sheep [edit]

Bas-relief from the palace of Tell Halaf, 9th century BC, showing a man slaughtering a sheep

Sheep (UDU/immeru(m)) were by far the most common farm brute in Mesopotamia and numerous types are attested in textual sources. They were well adapted to the small areas of pasture in the region, notably the areas of steppe, equally a issue of their ability to survive off very little nourishment. Small-scale farmers kept sheep, but the largest and best known flocks are those that were owned by institutions, which could consist of hundred or thousands of animals. Several different practices are attested. Often, they were placed on uncultivated land at the edge of the inhabited area in order to graze. At other times, they were fattened up in stables (especially sheep that were to be sacrificed to the gods), and transhumance was practiced with the stock of temples in southern Mesopotamia, who sent their herds out to the better pastures in central and northern Mesopotamia. Care of sheep was more often than not entrusted to specialists, who watched over the herds and were responsible for any lost animals. The animals were raised primarily for their wool, which was an essential cloth for Mesopotamian workshops, but as well for their meat and milk.[58] [59]

Cattle [edit]

Cattle (GU4 , alpu(yard) ) were more difficult to raise than sheep, but as well more valuable. They were an essential part of Mesopotamian agriculture, notably because of their role as beasts of burden. Their importance is shown by the fact that they are the just domestic animals that were sometimes given names by their owners. Several texts relating to institutional estates inform us of the care taken of them. Weaned calves were fed on forage equanimous of grain and reeds, and could be used to pull ploughs one time they reached three years of age. Different smaller animals, working cattle could not survive off the meagre Mesopotamian pasture land and thus they had to receive rations, like humans, and thus were more expensive to maintain. Some cattle were raised for their meat and cows were valued for their milk.[sixty] [61]

Other domestic animals [edit]

Goats (ÙZ, enzu(o)) were oftentimes raised along with sheep and were often found on smollholdings. They required less h2o than sheep, survived better in barren environments, but they were clearly non farmed on the same scale, because their skins were not as important to the Mesopotamian economy every bit sheep's wool and their meat likewise seems to accept been less valued. They were also milked.[62]

Among the four major domestic animals of the Nearly East, pigs (ŠAH, šahū(m)) had a special place, since they were raised for their meat and fat but lacked a major economical role. They yet seem to have been very widespread, existence raised in small-scale groups without much expense, at least until the 1st millennium BC, when they are mentioned in administrative texts less and less. In Neo-Babylonian times they are no longer present, and this disappearance is accompanied by the development of a negative moving picture of the animal in literary texts.[63]

Equids were domesticated belatedly in Mesopotamian history, with the donkey (ANŠE/imēru(o) ) only appearing clearly in the 4th millennium BC and the horse (ANŠE.KUR.RA/sīsu(one thousand)) arriving from elsewhere around the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. They were joined by the onager which could be tamed, and the mule. The donkey rapidly came to play an essential part as a beast of burden, allowing the development of a system of caravans for long-altitude transportation. The horse rapidly became a highly valued beast among the elites, specially warriors. The training of horses was the focus of a great deal of attending. The big areas of pasture in Mesopotamia are located in the due north, but pale beside the areas available outside Mesopotamia in western Iran and the Caucasus.[64] Starting effectually 2000 BC and especially in the 1st millennium BC, the dromedary and the camel (ANŠE.A.AB.BA/ibilu) were introduced and came to play an important role as beasts of burden and ship. Their meat and milk was as well consumed.[65]

Other domestic animals included the domestic dog (UR.GI7 , kalbu(m)), and those used past rulers for hunting were the object of special attention. Farmyard birds attested from the beginning of Mesopotamian history include geese, ducks, and pigeons. Chickens were introduced from India late in the period, effectually the first of the 1st millennium BC. Poultry were mainly raised for their meat and their eggs.[66] [67] Finally, apiculture was developed in Mesopotamia at the starting time of the 1st millennium BC. Before this, beloved and beeswax were nerveless from wild hives.[68]

[edit]

Hunting and fishing [edit]

Human exploitation of the Mesopotamian surroundings also involved some activities which do not fall into the classes of agronomics or animal husbandry, only which are related to them. Hunting and fishing were of import, primarily as a source of food, but by the historical period they played a secondary role compared to animal husbandry. There were specialist hunters and fishers employed by major institutions, but regular people besides engaged in both activities. At that place were many wild animals that could exist killed or captured: gazelles, goats, cattle, boar, foxes, hares, diverse birds, and even insects, every bit well equally a large variety of fish which could be caught in the swamps, rivers, canals, and at sea in the Farsi Gulf.[69] [70]

Reeds and timber [edit]

The numerous swamps in the south part of Mesopotamia supplied diverse kinds of reed (peculiarly Phragmites australis) in great quantity. Reeds were collected for various purposes, notably the construction of buildings (huts, palisades, reinforcing chains in mud-brick walls, etc.), boats, baskets, and the reed pens used for inscribing cuneiform into dirt tablets.[71]

Mudhif is a traditional reed house built for at least 5,000 years, southward of Iraq.

Aboriginal Mesopotamia besides had an observable supply of timber, which has since largely disappeared as a outcome of over-exploitation. Most prominent were the appointment-palms, simply there were also poplars, tamarisks, willows, junipers, and others, which were used for their wood as well equally their fruit, wherever possible. This local timber was mainly used in small-calibration structure; the swell palaces and temples, also every bit luxury wooden items, required quality timber imported from further afield (cedar of Lebanon, ebony, cypress, etc.). These strange trees could besides exist planted in Mesopotamia (arboriculture), with stands of foreign timber attested in the south from the end of the 3rd millennium BC.[72] Teams of lumberjacks were sent to tend to and harvest the forests of major institutions at the commencement of spring and autumn.[73]

Economical organisation of agriculture and animal husbandry [edit]

Reconstructing the system of the ancient economy from the surviving sources (mainly textual) faces numerous difficulties. Agricultural activity in ancient Mesopotamia is documented by tens of thousands of administrative documents, but they by and large chronicle to a specific sector of the economy - the institutions of the royal palace and the temples, and, to a bottom degree, the individual domains of the elites. It is their activities and initiatives which are the main source of data, and ane of the ongoing debates in scholarship is whether they are representative of the majority of agronomical action or if a large portion of the agricultural economy is unknown to us because it never required the production of written documentation. The theoretical models used to attempt to reconstruct how the Mesopotamian economy functioned and the goals of its actors thus play a decisive role in scholarly work. It appears, at any rate, that agriculture and animal husbandry involved a large office of the human resources of Mesopotamia, created various complex connections betwixt individuals through different formal and breezy agreements, and provided a large role of what was necessary for Mesopotamian society's subsistence.

Theoretical models [edit]

Analysis of ancient Mesopotamian society and its economy poses various problems of interpretation, when one attempts to operate at the general level of reconstructing the principles that guided the activities and choices of actors. Theoretical assumptions of researchers - even if unstated - have tended to guide their interpretations. Early in the history of study of cuneiform documents, there were attempts to apply frameworks developed from the study of other civilizations, which is especially notable in analyses of Mesopotamian order which describe it as "feudal"[74] and in interpretations inspired past Marxist theories of the economy (especially the thought of the "Asiatic fashion of production").[75] [76] [77] The approach of Max Weber has likewise provided some useful interpretations.[78] [79]

But the key opposition in the analysis of ancient economies is the dichotomy betwixt "formalists" and "substantivists", which is related to an earlier dichotomy between "modernists" and "primitivists".

The "formalist" model is based on the hypotheses of the neoclassical economics. It considers whether economic agents were or were not "rational", i.due east. consumers are motivated past the goal of maximising their utility and producers by the goal of profit maximization. Co-ordinate to this model, the economy follows timeless, universal laws, the market exists in all societies and, in optimal conditions of pure and perfect competition, prices are fixed by supply and demand, permitting an efficient resource allotment of the means of product, and Pareto efficiency. In this example, one could use the tools of modern economic analysis to study aboriginal economies, which is why this position is characterised every bit "modernist".[80] [81]

By contrast, the substantivist model derives from the works of Karl Polanyi, who idea that pre-industrial economies were embedded in society and thus different civilizations had their own economical systems, not universal economic laws, and thus they could not be studied outside of their social context. On this point of view, individuals had their ain "rationality" that would not exist establish in other societies in the same form.[82] [83] [84] In this case, modern economical tools were non necessarily in operation and other factors similar redistribution, reciprocity, and exchange must exist considered outset. Some researchers of this movement like J. Renger would even exclude the thought of profit in the ancient globe at all, claiming that the ancients utilised surpluses solely to increase their prestige and to serve the cult of the gods.[85]

This clarification of models stand for extreme cases for their explanatory value, but in fact scholars studying the Mesopotamian economy rarely prefer such extreme positions. As M. Van de Mieroop recognises, there are many scholars who utilize tools of contemporary economic analysis on the ancient economic system, while taking account of the specific details of the societies in question.[86]

Notes [edit]

- ^ For attempts at holistic reconstruction of the Sumerian agronomical yr, meet: LaPlaca & Powell 1990, pp. 75–104, The Agricultural Bike and the Calendar at Pre-Sargonic Girsu and Hruška 1990, pp. 105–114, Das landwirtschaftliche Jahr im alten Sumer: Versuch einer Rekonstruktion.

References [edit]

- ^ a b Cowan, C. Wesley; Watson, Patty Jo, eds. (2006). The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective. The University of Alabama Printing. ISBN9780817353490.

- ^ Sanlaville 2000, pp. 65–69.

- ^ F. Joannès, "Tigre" & "Euphrate" in Joannès 2001, pp. 851–ii, 323–325

- ^ P. Sanlaville, "Considérations sur fifty'évolution de la Basse Mésopotamie au cours des Derniers millénaires," Paléorient 15/2, 1989, p.v-27.

- ^ P. Sanlaville & R. Dalongeville, "L'évolution des espaces littoral du Golfe Persique et du Golfe domain Depuis la phase finale de la transgression post-glaciaire," Paléorient 31/ane, 2005, pp. 19-20

- ^ Sanlaville 2000, pp. 99–104.

- ^ Potts 1997, pp. fourteen–fifteen.

- ^ Sanlaville 2000, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Huot 1989, pp. 82–83.

- ^ M. Sauvage, 'Culvert,' in Joannès 2001, pp. 155–159

- ^ Postgate 1992, pp. 173–183

- ^ F. Joannès, "Irrigation," in Joannès 2001, pp. 415–418

- ^ See the dossier in J.-K. Durand, Les Documents épistolaires du palais de Mari, Volume II, Paris, 1998, p. 572-653.

- ^ B. Lafont, "Irrigation Agriculture in Mari," in Jas 2000, pp. 135–138.

- ^ B. Lafont, "Cadastre et arpentage," in Joannès 2001, pp. 149–151

- ^ Yard. Liverani, "Reconstructing the Rural Mural of the Ancient Near Eastward," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 39 (1996) p. 1-49

- ^ Postgate 1992, pp. 158–159 & 173–174.

- ^ B. Hruška, "Agricultural Techniques," in Leick 2007, p. 58

- ^ B. Lafont, "Irrigation Agronomics in Mari," in Jas 2000, pp. 130–134

- ^ T. J. Wilkinson, "The Structure and Dynamics of Dry-Farming States in Upper Mesopotamia," Current Anthropology 35/5, 1994, p. 483-520

- ^ T. J. Wilkinson, "Settlement and State Use in the Zone of Incertitude in Upper Mesopotamia" in Jas 2000, pp. iii–35

- ^ C. Zaccagnini, The Rural Landscape of the Land of Arraphe, Rome, 1979.

- ^ T. J. Wilkinson, J. Ur, E. Barbanes Wilkinson & M. Altaweel, "Landscape and Settlement in the Neo-Assyrian Empire," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 340 (2005) p. 23-56.

- ^ F. Chiliad. Fales, "The Rural Landscape of the Neo-Assyrian Empire: A Survey," State Archives of Assyria Bulletin Iv/two, 1990, pp. 81-142.

- ^ G. van Driel, "On Villages," in West. H. van Soldt (ed.), Veenhof Anniversary Volume: Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of His Threescore-fifth Birthday, Leyde, 2001, p. 103-118

- ^ P. Steinkeller, "City and Countryside in Third Millennia Southern Babylonia," in Eastward. C. Rock (ed.), Settlement and Society: Essays dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams, Chicago, 2007, p. 185-211

- ^ S. Richardson, "The World of the Babylonian Countryside," in Leick 2007, pp. 13–38 focusses on the relationship between boondocks and country but likewise provides some information on rural settlement.

- ^ H. Wright, The Assistants of Rural Production in an Early Mesopotamian Town, Ann Arbor, 1969.

- ^ A. Invernizzi, "Excavations in the Yelkhi Surface area (Hamrin Project, Republic of iraq)," Mesopotamia 15, 1980, p. 19-49

- ^ R. Chiliad. Boehmer & H.-Due west. Dämmer, Tell Imlihiye, Tell Zubeidi, Tell Abbas, Mainz am Rhein, 1985 (note conclusions p. 32-35).

- ^ a b B. Hruška, "Agronomical Techniques," in Leick 2007, p. 59

- ^ Huot 1989, pp. 92–98.

- ^ B. Panthera leo & C. Michel, "Insectes," in Joannès 2001, p. 412

- ^ Potts 1997, p. 75.

- ^ A. Sherratt, « Plough and pastoralism: aspects of the secondary products revolution », in I. Hodder, G. Isaac et N. Hammond (ed.), Pattern of the Past: Studies in honour of David Clarke, Cambridge, 1981, p. 261–305

- ^ Due west. Van Zeist, "Plant Tillage in Ancient Mesopotamia: the Palynological and Archeological Approach," in Klengel & Renger 1999, pp. 25–42

- ^ C. Becker, "Der Beitrag archäozoologischer Forschung zur Rekonstruktion landwirtschaftlicher Aktivitäten: ein kritischer Überblick" in Klengel & Renger 1999, pp. 43–58

- ^ Thousand. A. Powell, "The Sumerian Agriculture Group: A Brief History," in Klengel & Renger 1999, pp. 291–299

- ^ Potts 1997, pp. 57–62.

- ^ B. Lion & C. Michel, "Céréales," in Joannès 2001, pp. 172–173

- ^ Translation: etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.united kingdom ; commentary in Southward. N. Kramer, 50'histoire embark à Sumer, Paris, 1993, p. 92-95

- ^ Postgate 1992, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Potts 1997, pp. seventy–86.

- ^ B. Lion & C. Michel, "Céréales," in Joannès 2001, p. 173

- ^ B. Hruška, "Agricultural Techniques," in Leick 2007, pp. 59–61

- ^ F. Joannès, "Palmier-dattier," in Joannès 2001, pp. 624–626

- ^ Stol 1984, pp. 127–139.

- ^ F. Joannès, "Lin," in Joannès 2001, pp. 472–473

- ^ Potts 1997, pp. 67–68.

- ^ B. Lion, "Sésame," in Joannès 2001, p. 778

- ^ Postgate 1992, p. 170-172.

- ^ J. Grand. Renfrew, "Vegetables in the Ancient Near Eastern Diet," in Sasson 1995, pp. 191–195

- ^ Potts 1997, p. 62-66 & 69-70.

- ^ C. Michel, "Cultures potagères," in Joannès 2001, pp. 213–215

- ^ C. Michel & B. Lion, "Arbres fruitiers," in Joannès 2001, pp. 70–71

- ^ J.-P. Brun, Archéologie du vin et de fifty'huile, De la Préhistoire à l'époque hellénistique, Paris, 2004, pp. 46-47 & 131-132

- ^ M. A. Powell, "Wine and the Vine in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Cuneiform Evidence," in P. E. McGovern et al. (ed.), The Origins and Ancient History of Wine, Amsterdam, 1997, pp. 97–122.

- ^ Postgate 1992, p. 159-163.

- ^ B. King of beasts & C. Michel, "Ovins," in Joannès 2001, pp. 610–612

- ^ Postgate 1992, p. 163-164.

- ^ B. King of beasts, "Bovins," in Joannès 2001, pp. 142–143

- ^ B. Lion & C. Michel, "Chèvre," in Joannès 2001, pp. 180–181

- ^ B. King of beasts & C. Michel, "Porc," in Joannès 2001, pp. 670–671

- ^ B. Lafont, "Équidés," in Joannès 2001, pp. 299–302

- ^ B. Hesse, "Animal Husbandry and Human Nutrition in the Ancient Nearly East," in Sasson 1995, p. 217

- ^ B. Panthera leo & C. Michel, "Animaux domestiques," in Joannès 2001, pp. 49–fifty

- ^ B. Lion & C. Michel, "Oiseau," in Joannès 2001, pp. 603–606

- ^ C. Michel, "Miel," in Joannès 2001, p. 532

- ^ B. Panthera leo, "Chasse," in Joannès 2001, pp. 179–180

- ^ B. Panthera leo & C. Michel, "Pêche," in Joannès 2001, pp. 638–640

- ^ Thousand. Sauvage, "Roseau," in Joannès 2001, pp. 735–736

- ^ W. Heimpel, "Xx-Viii Copse Growing in Sumer," in D. I. Owen (ed.), Garšana Studies, Bethesda, 2011, p. 75-152.

- ^ C. Castel & C. Michel, "Bois," in Joannès 2001, pp. 135–138

- ^ S. Lafont, "Fief et féodalité dans le Proche-Orient ancien," in J.-P. Poly et Due east. Bournazel (ed.), Les féodalités, Paris, 1998, p. 515-630

- ^ Van de Mieroop 1999, p. 111-114.

- ^ Graslin-Thomé 2009, p. 106-109.

- ^ C. Zaccagnini, "Modo di produzione asiatico e Vicino Oriente antico. Appunti per una discussione," Dialoghi di archeologia NS three/iii, 1981, pp. 3-65.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 1999, p. 115.

- ^ Graslin-Thomé 2009, p. 102-106.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 1999, pp. 120–123.

- ^ Graslin-Thomé 2009, pp. 119–131.

- ^ On Polanyi's contributions to assyriology, see the articles of P. Clancier, F. Joannès, P. Rouillard and A. Tenu (ed.), Autour de Polanyi, Vocabulaires, théories et modalités des échanges. Nanterre, 12-xiv juin 2004, Paris, 2005

- ^ Van de Mieroop 1999, pp. 116–118

- ^ Graslin-Thomé 2009, pp. 110–118.

- ^ J. Renger, "Trade and Market in the Ancient Near East: Theoretical and Factual Implications," in C. Zaccagnini (ed.), Mercanti eastward politica nel mondo antico, Rome, 2003, pp. 15-forty; J. Renger, "Economy of Ancient Mesopotamia: A Full general Outline," in Leick 2007, pp. 187–197

- ^ Van de Mieroop 1999, pp. 120–121.

Bibliography [edit]

- Bottéro, J.; Kramer, South. N. (1989). Lorsque les Dieux faisaient 50'Homme. Paris. ISBN2070713822.

- Charpin, D. (2003). Hammu-rabi de Babylone. Paris. ISBN2130539637.

- Englund, R. Thou. (1998). "Texts from the Late Uruk Period". In J. Bauer, R. K. Englund & Thousand. Krebernik (ed.). Mesopotamien, Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. Fribourg et Göttingen. pp. 15–233. ISBN3-525-53797-ii.

- Garelli, P.; Durand, J.-M.; Gonnet, H.; Breniquet, C. (1997). Le Proche-Orient asiatique, tome 1 : Des origines aux invasions des peuples de la mer. Paris.

- Garelli, P.; Lemaire, A. (2001). Le Proche-Orient Asiatique, tome 2 : Les empires mésopotamiens, Israël. Paris.

- Grandpierre, V. (2010). Histoire de la Mésopotamie. Paris.

- Graslin-Thomé, L. (2009). Les échanges à longue distance en Mésopotamie au Ier millénaire : une approche économique. Paris.

- Huot, J.-L. (1989). Les Sumériens, entre le Tigre et l'Euphrate. Paris.

- Jas, R. G. (2000). Rainfall and agriculture in Northern Mesopotamia. Istanbul.

- Joannès, F. (2000). La Mésopotamie au Ier millénaire avant J.-C. Paris.

- Joannès, F. (2001). Dictionnaire de la civilization mésopotamienne. Paris.

- Klengel, H.; Renger, J. (1999). Landwirtschaft im Alten Orient. Berlin.

- Lafont, B. (1999). "Sumer, II. La société sumérienne, i. Institutions, économie et société". Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible fasc. 72.

- Lafont, Bertrand; Tenu, Aline; Clancier, Philippe; Joannès, Francis (2017). Mésopotamie: De Gilgamesh à Artaban (3300-120 av. J.-C.). Paris: Belin. ISBN978-2-7011-6490-8.

- LaPlaca, P. J.; Powell, Marvin A. (1990). "The Agronomical Cycle and the Calendar at Pre-Sargonic Girsu". In Postgate, J. N.; Powell, M. A. (eds.). Irrigation and Cultivation in Mesopotamia Part II. Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture v. Cambridge: Sumerian Agriculture Grouping. pp. 75–104.

- Leick, Thousand. (2007). The Babylonian Globe. Londres et New York.

- Potts, D. T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Londres.

- Postgate, J. Due north.; Powell, K. (1984–1995). Message of Sumerian Agronomics. Cambridge.

- Postgate, J. N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia, Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Londres et New York.

- Postgate, J. Due north. (2007). The Land of Assur & The Yoke of Assur, Studies on Assyria 1971-2005. Oxford.

- Sanlaville, P. (2000). Le Moyen-Orient arabe, Le milieu et 50'homme. Paris.

- Sasson, J. M. (1995). Civilizations of the Aboriginal About East. New York.

- Van de Mieroop, Chiliad. (1999). Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History. Londres et New York.

- Stol, Martin (1984). "Beans, Peas, Lentils and Vetches in Akkadian Texts". Message on Sumerian Agronomics. 2: 127–139.

- Westbrook, R. (2003). A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law. Leyde.

- Wiggerman, F. A. M. (2011). "Agronomics as Culture: Sages, Farmers and Barbarians". In Yard. Radner et Eastward. Robson (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Oxford et New York.

- Hruška, B. (1990). The Agricultural Year in Aboriginal Sumer: An Attempt at Reconstruction [Das landwirtschaftliche Jahr im alten Sumer: Versuch einer Rekonstruktion]. Message on Sumerian Agriculture 5 (in German). Cambridge: Sumerian Agronomics Group. pp. 105–114.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Mesopotamia

Posted by: colliercatry1936.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Why Were Goats Only Domesticated In Mesopotamia? What Made This Animal Useful?"

Post a Comment